Does

living naked make you a savage? Certainly not in the case of the Amazon’s

Yanomami Indians. But have a look at the images that follow, and decide whether

you see any naked savagery.

There

are savages in the Amazon, but they wear clothes.

Living

in yanos, or shabanos, communal houses sheltering up to 100 people, each family

around its own fire, the Yanomami have an equalitarian and perfectly organized

society. They look after their clans’ most vulnerable members and share with

everyone the game they hunt, keeping for themselves only the least attractive

parts. They raise their kids with as much love, but with more wonderful results

than many of us achieve. Their children are the happiest I have seen anywhere in

a life of foreign travel. And their teenagers would not even think of raising problems.

What

to my eyes prove the Yanomami’s great intelligence and right to sit at the

table of civilized people is their amazing sense of humor. While I shared their

lives for a month, they made me laugh every day.

Thanks

to Bruce Albert, a French anthropologist who speaks the Yanomami language, I always

knew what the Indians were saying or what they were planning. So I never missed a funny remark or a great photo

opportunity. Bruce has dedicated his adult life to study and help protect the

Yanomami against predatory and criminal outsiders.

There

was a third man with Bruce and I among the Yanomami. Robin Hanbury-Tenison,

British explorer and author of many books, he also was, and is, the founder of

Survival International, a charity dedicated, with impressive results, to the defense of tribal people’s

rights. In 1982 Time-Life Books had assigned the three of us, each one in his

own specialty, to produce one of the books of their People of the Wild series. It would be titled Aborigines of the Rain Forest: the Yanomami. The book sold out

within a few months.

Bruce

told me that our Yanomami friends had given us totems, all based on their keen observations

of us. Mine was Tapir. For three reasons.

1 - Because

the tapir is the forest’s biggest animal. I was big next to them.

2 - Because

the tapir never sleeps.” (I hit my hammock later than them, photographing them resting around their family fires. To do so I also got up before

dawn. Sometimes I woke up in the middle of the night to switch on my

flashlight and jot down some notes).

3 - Because

the tapir can turn into thunder. This was about my good-heartedly loud laugh, which the many

residents around the yano apparently enjoyed and never failed to acknowledge by

always echoing it, though on a much higher pitch).

But

back to clothes-wearing savages. Contrary to the Yanomami, who live very happy

lives with no interest in money and what it can buy, those other men are criminally

greedy. So much so that, if allowed, they would happily kill every one of the

20,000 Yanomami living on both sides of the Brazil-Venezuela border to take

possession of their land. And they have already killed many. And they have also

burned down vast stretches of the Amazon

forest.

Those

savages are gold miners and owners of businesses dealing in large-scale logging,

cattle rearing, and agriculture—all of them illegally.

View the photographs below, following the French translation

Est-on sauvage pour vivre nu ? Certainement pas dans le cas des

Yanomamis de l’Amazonie. Mais jetez un coup d’œil sur les photos qui suivent et

décidez-vous-mêmes si vous y voyez de la sauvagerie.

L’Amazonie a ses sauvages, mais ils cachent leurs bas instincts sous des vêtements.

Les Yanomamis vivent dans des maisons communales connues comme yanos

ou shabonos. Elles abritent jusqu’à

100 personnes, chaque famille autour de son propre feu. La société de ces Indiens est égalitaire et parfaitement

organisée. Elle assure le bien-être de ses membres les plus vulnérables et ses

chasseurs partagent leur gibier, ne gardant pour eux-mêmes que ses parties les

moins attractives. Ils élèvent leurs enfants avec autant d’amour mais avec de

bien meilleurs résultats que beaucoup d’entre nous. Leurs enfants sont les plus

heureux de tous ceux que j’ai photographiés durant une vie de voyages

internationaux. Quant à leurs adolescents, il ne leur viendrait pas à l’esprit

de causer des problèmes.

Ce qui a mes yeux ajoute au droit des Yanomamis de s’asseoir à la table des

sociétés civilises est leur profonde intelligence et leur étonnant sens de l’humour.

Vivant entre eux durant un mois, ils m’ont fait rire constamment.

Grâce à Bruce Albert, un anthropologue français qui parle couramment le

Yanomami, Je sus toujours ce qui se disait autour de nous et ce qui se

préparait. Je ne perdais jamais un bon mot et étais toujours prêt à suivre un

groupe ou l’autre pour les photographier à la chasse, à la cueillette, aux

champs, a la recherche de poison végétal pour leurs flèches, ou de la drogue

qui donne aux chamanes la possibilité de communiquer avec les esprits.

Bruce a consacré sa vie adulte à étudier et aider à protéger les Yanomamis

contre les dangers constants que représente le monde moderne qui menace leur

agreste culture. Les Yanomamis le vénèrent.

Le britannique Robin Hanbury-Tenison complétait notre équipe. Explorateur

et auteur de nombreux livres, il était, et est, le fondateur de Survival

International, qui depuis plusieurs décades lutte avec énorme succès pour la

défense des peuples tribaux.

En 1982 Time-Life Books nous avait confié la mission de ramener le matériel

d’un livre pour leur série intitulée People

of the Wild (Peuples des terres sauvages). Son titre fut Aborigines of the Rain Forest : the

Yanomami (Aborigènes de la forêt: les Yanomamis).

Bruce m’apprit que nos amis Yanomamis nous avaient donnés un totem. Le mien

était tapir. Pourquoi Tapir ? Pour trois raisons, m’expliqua-t-il.

« Car le tapir est l’animal le plus grand et robuste de la forêt ».

( Je l’étais comparé à eux).

« Car le tapir ne dort jamais ». (Je me couchais tard pour les

photographier, couchés dans leurs hamacs autour des feux. Ou je me réveillais la nuit pour allumer ma lampe et

ajouter quelques notes à mon journal.

« Et car le tapir peut se transformer en tonnerre » (le tonnerre

était mon rire sonore, qui déclenchait le rire de tous les résidents, quoique

sur un ton considérablement plus aigu).

Pour en revenir aux vrais sauvages, et contrairement aux Yanomamis, qui ne

demandent que de vivre leur vie bucolique en paix et sans soucis d’argent et

des articles qu’il permet d’obtenir, ces autres hommes sont d’une rapacité que

rien n’arrête. A tel point que s’ils en avaient la permission ils tueraient

volontiers chacun des quelque 20,000 Yanomamis qui vivent de part et d’autre de

la frontière séparant le Brésil du Venezuela pour s’emparer de leurs terres.

Ils en ont déjà tués beaucoup. Ils raseraient aussi la forêt, qui a déjà

souffert lourdement entre leurs mains. Ces sauvages sont les chercheurs d’or et

les propriétaires de compagnies forestières, agriculturales et d’élevage de bétail

à grande échelle—tous illégaux.

Yanomami father decorating his baby son with bird

down.

Père

Yanomami décorant la tête de son petit garçon avec du duvet d’oiseau.

Grandfather

Grand’père

Father of one and grandfather of two

Père d’un

enfant et grand’père des deux autres

Father and son. Boy is eating manioc flat bread.

Mother and baby in hammock.

Mother and baby in the forest.

Doesn’t this remind you of your own childhood?

Cette image

ne vous rappelle-t-elle pas votre propre enfance ?

Mother showing baby daughter the fish she caught.

Mère

montrant à sa petite fille le poisson qu’elle a pêché.

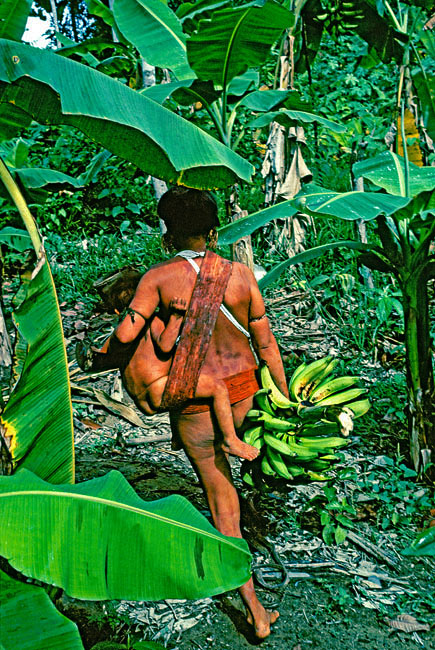

Mother bringing home a bunch of plantain, a banana that can be eaten only cooked, from her forest

garden.

Mère ramenant

à son feu des bananes à cuire de son jardin de la forêt.

Mother bringing home manioc from her garden and water

from the river.

Mère ramenant du manioc de son jardin et de l’eau de la rivière.

Father bathing

with his son

Père se

baignant avec son fils

Helping a young member of the clan to cross a river

Aidant une petite

fille du clan à traverser une rivière

Having breathed a narcotic powder to help them get in

touch with spirits, two shamans strive to pull malaria out of a small sick boy.

Malaria was introduced by illegal gold miners.

Ayant aspiré

une poudre narcotique afin de communiquer avec les esprits, deux chamanes s’efforcent

d’arracher la malaria du petit garçon. Des chercheurs d’or illégaux ont

introduit ce fléau.

Bruce Albert

in 1982

Bruce Albert

en 1982