Because the geological

expedition I had to photograph was being delayed, I traveled to Tendaho, a

dusty town at the southern end of the Danakil Depression in the Aussa Danakil

sultanate. Here were the fiercest Danakil, and their scrutinizing eyes made me

feel virtually naked. It was evident that I must have looked like some freakish

blunder of nature.

In those days a Danakil man wanting to

marry still had to kill a man, emasculate him, and offer his trophy to the

woman he wanted. It proved his virility, which in this infernal country was

indispensable to the survival of a family.

An

Ethiopian official warned me not to leave the village without a letter from the

sultan. Unfortunately he was absent. After searching for a possible

interpreter, I had to settle on a 53-year-old Moslem named Mahmud, who spoke

Danakil and Italian. He did not speak English, but understood some. I did not

speak Italian, but understood some. Mahmud went to ask a balabat, or local chieftain, for his protection.

The next morning there would be an

important market in Aisayita, a small town 35 miles (56 kilometers) to the east,

which would attract many Danakil. To get there on foot in time we left that

very night. The balabat lent us two men to guide us and two two camels to carry

our luggage and water.

Towards 4:00 a.m., five armed Danakil

warriors emerged from the darkness to have a close look at me. One of them

tested my biceps, commented on the vigor of my handshake, deluged Mahmud with

questions about me, the ferengi, or

foreigner , and asked us for cigarettes (though a non-smoker, I always carried

some). While those men nailed us there for a while, our two guides moved on

ahead. Then, with that same man holding my hand, we walked together for a while,

though too slowly to catch up with our guides.

Not long after the five Danakil had

finally drifted away, the dark nightmarish desert produced four new

warriors--younger and evil-looking. They

too assailed Mahmud with questions as we kept walking. Over the next 15 minutes

or so their voices behind me got louder and louder, with the word ferengi

bouncing back and forth. And there was disturbing tussle. Pretending to be unaware of what was

happening in my back, I did not allow myself to look around as I kept walking.

Doing so would have forced me to interfere, stopping the march, and putting us

at even greater risk.

But at some point

Mahmud could no long contain his tormentors.

“Make trouble! Make trouble!” Mahmud cried,

his voice shaking with rage and anguish. “I know, Mahmud” I replied. “But

please let’s keep calm.” Still, I started wondering whether my manhood would

end up hanging in a woman’s tent or from a horse’s bridle, as was the custom.

When Mahmud was pushed against me, just as

our two guides had finally become visible and Mahmud was crying for their help,

I turned around to see that one of the men had unsheathed his large curved

knife. Fortunately, our two guides, animated by a devilish fury, came rushing

back, shouting what must have been insults and perhaps the name of the balabat,

our Tendaho protector. Sheepishly, though chuckling to keep face, our

tormentors walked away.

Mahmud’s face was ashen (I could not see

my own), and for an hour or so I could not get anything out of him. Finally, he

told me that the Danakil had grabbed our cigarettes and a box of biscuits he

was carrying for breakfast. When a man asked him what I carried in my camera

bag, Mahmud warned him that my people would seek revenge on him if they harmed

me in any way. But he had found this amusing.

“This man carries no gun and has no armed escort,” he said. “He’s a nobody, and no one will

come looking for him after we kill him—and you.” When he was going to pull my

camera bag from my shoulder, Mahmud hit his hand with the stick that Ethiopians

always carry around. At that, the man had pushed him and pulled his knife.

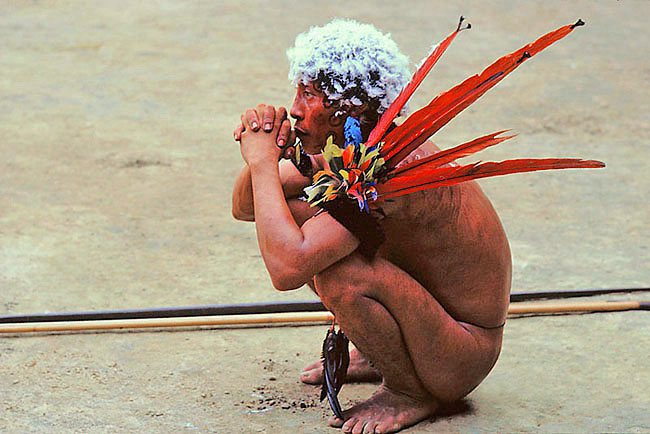

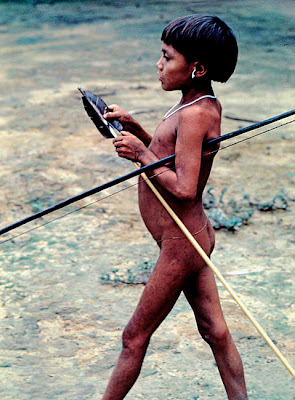

At Aisayita, which was crowded with

heavily armed Danakil men, I photographed many. Ignoring their suspicious eyes,

and working quickly from one man to the next, I pretended it was the most

normal thing in the world and got away with it. Later I would spend some time

documenting the daily life of some Danakil encampments.

When I returned to Makale once more, I

found the geologists installed at the hotel. I thought I was safe now. But my

recklessness would see to it that my adventures were only just beginning. I’ll tell you about them

in other posts.

View photos below, following French translation.

****************************

Comme l’expédition

géologique que je devais photographier n’arrivait pas, je voyageai à Tendaho,

un gros village poussiéreux au sud de la dépression Danakil dans le sultanat

des Danakil Aussa. Beaucoup de ces Danakil pratiquaient encore la fâcheuse

coutume qui exigeait de l’homme en quête d’épouse de tuer d’abord un autre

homme, de l’émasculer et d’offrir à sa bien-aimée le trophée qui prouverait sa

virilité, indispensable pour assurer la survie d’une famille dans ce pays

infernal.

A Tendaho les hommes Danakil, armés de

vieux fusils et d’énormes couteaux courbes, m’entouraient de toutes parts.

M’observant avec des yeux peu amicaux et hésitant à me céder le pas sur les

allées de sable, ils me faisaient sentir

aussi nu qu’à la naissance. Il était évident que je devais être à leurs

yeux une sérieuse anomalie de la nature—blond, yeux bleus, rouge de la brulure

du soleil… (Un an plus tard, chez les Dayak de la jungle de Bornéo, mes yeux

bleus me donneraient une certaine aura. Mais pas ici).

Un fonctionnaire éthiopien m’avertit que

je mettrais ma vie en danger si j’abandonnais le village sans une lettre de

recommendation du sultan. Mais le sultan était absent. Le fonctionnaire me

présenta un Musulman de 53 ans qui parlait le Danakil et l’Italien. Il ne

parlait pas l’Anglais, mais le comprenait un peu. Je parlais l’Anglais et

comprenais un peu l’Italien. En fait d’interprète, je ne trouverais pas mieux à

Tendaho et l’acceptai.

Mahmud me conduisit chez un balabat, un chef local. Le balabat me déclara sous

sa protection et me trouva deux hommes Danakil pour nous guider dans le désert

et deux chameaux pour transporter nos bagages et notre eau.

Nous partîmes à pied la nuit même--pour

éviter la chaleur du jour, mais aussi pour arriver à Asayita, 56 kilomètres à

l’est de Tendaho, le matin suivant. Un grand marché nous y attendait, visité

par de nombreux Danakil.

Vers quatre heures du matin, cinq

guerriers Danakil émergèrent de la nuit. Commentant bruyamment notre rencontre,

ils assommèrent Mahmud de questions à mon sujet et demandèrent des cigarettes

(quoique non-fumeur j’en avais toujours avec moi). L’un des hommes tata mes

biceps et se déclara satisfait de la vigueur de ma main, qu’il ne lâcha

pas. Finalement, nous ayant fait perdre

beaucoup de temps sur place tandis que nos deux guides Danakil continuaient

leur chemin, bien en avant dans la nuit opaque, nous reprîmes la marche tous

ensemble, moi main dans la main du bonhomme, quoique trop lentement pour rattraper nos guides

Au bout de 20 minutes nos cinq Danakil

nous quittèrent. Mais bientôt en apparurent quatre autres, plus jeunes et l’air beaucoup plus sauvage et agressif. Il

devint tout de suite évident que les choses n’iraient plus aussi facilement. Mais

cette fois je ne m’arrêtai pas, ni ralentis la marche. Derrière moi les

questions des Danakil, ou le mot ferengi (étranger) rebondissait constamment,

sonnait avec une violence croissante. Je me rendais compte qu’on se bousculait

dans mon dos, mais prétendais ne pas le savoir. J’espérais donner l’impression

d’être trop important pour avoir á me préoccuper de ma sécurité. Mais espérant

rejoindre nos guides, je m’efforçais d’allonger le pas sans y attirer

l’attention. Avec eux nous serions quatre contre quatre, quoique non armés

nous-mêmes. Par contre, m’arrêter de marcher pour me mêler à la dispute nous

ferait perdre encore davantage de terrain sur nos guides. Finalement, Mahmud n’en

put plus.

« Make trouble ! Make

trouble ! » cria-t-il dans son Anglais rudimentaire. « Je

sais, » lui répondis-je sans me retourner ni ralentir le pas. « Mais

garde le calme si tu peux.» Cependant je commençais à me demander si ma

virilité terminerait bientôt accrochée dans la tente d’une femme ou à

l’encolure d’un cheval, ou ces articles terminaient généralement.

Quand un Danakil poussa Mahmud violemment contre

moi, je n’eus d’autre option que de me

retourner. Un Danakil avait dégainé son énorme couteau, large comme ma main.

Cette fois, d’une voix angoissée, Mahmud

appela nos guides. Heureusement, et quoiqu’invisibles dans l’obscurité, ils

n’étaient plus loin. Abandonnant leurs chameaux ils vinrent á grands cris nous

arracher des mains de ces sauvages. Ce qu’ils crièrent à nos tourmenteurs leur

quitta immédiatement toute arrogance, et penauds ils retournèrent à la nuit.

Le

visage du pauvre Mahmud était de cendre (je ne pourrais dire de quelle couleur

était le mien, moi qui n’avais pas vu le danger d’aussi près que lui). Durant

une heure il ne put ouvrir la bouche. Finalement il parla.

D’abord les Danakil avaient arraché de ses

mains nos cigarettes et les biscuits que nous nous réservions pour la faim.

Quand plus tard l’un d’eux allait s’emparer aussi de la sacoche photographique

qui pendait de mon épaule Mahmud le frappa de son bâton, ce qui les mit tous en

colère. Mahmud leur prédit des représailles féroces de la part de mes gens

s’ils me faisaient du mal. Mais ses paroles les avaient amusés. « Un homme

qui voyage sans escorte et sans armes ne peut être qu’un pauvre diable. »

dirent-ils. « Nous allons tuer cet

homme, et toi avec lui, et personne ne se donnera la peine de vous

chercher. »

Je passai la journée suivante au marché à

photographier les Danakil, tous fortement armés. Ignorant leurs regards méfiants,

j’agis comme si c’était la chose la plus normale du monde, mais passant d’un

homme a l’autre très rapidement. Plus tard je documenterais la vie quotidienne

de quelques campements. De retour à Makale, je trouvai les géologues installés

à l’hôtel.

Je croyais mes aventures terminées, mais j’étais

bien trop insouciant m’en livrer si tôt. En fait elles n’avaient que commence

Je les raconterai prochainement.